Royal Signals Museum,

Blandford Camp, Dorset, England

By Roy Stevenson

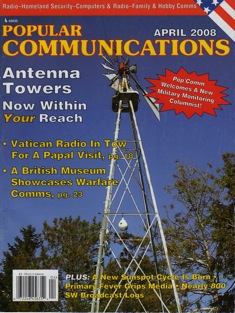

A Saracen Armored Command vehicle and an AFV439 Armored Communications Vehicle guard the parking lot outside the Royal Signals Museum. The large, gray, metal-walled museum opened in 1997, to show the history of the Royal Corps of Signals. It’s also a crash course on the science and technology of military communications from the Crimean War to the Gulf War.

Providing marvelous insight into a relatively downplayed area of military operations, the Royal Signals Museum tells about the men and women who operate signaling equipment, and their contribution to England’s history in the past 150 years. A great selection of books, souvenirs, and gifts about military signals and radios is found in the bookstore by the front entrance.

There’s enough radios and communications equipment displayed here to qualify it for nirvana status for radio and signals enthusiasts. In addition, some unknown but fascinating aspects of military communications are covered such as Women at War, Behind Enemy Lines (The Special Operations Executive Story), D-Day, Special Forces, Animals at War, Dispatch Riders, military signaling vehicles, antique signaling equipment and much more.

A mixture of reader boards and display cases tell the general history of military communications, in the first displays. Runners provided the first form of long-distance signaling, then men on horseback. Another primitive but effective method of signaling used chains of soldiers on hilltops shouting messages to each other. The Persian King Darius set up such a chain in the 5th century BC. Drums and trumpets were also used. The Greeks had a torch telegraph system and the Romans used colored smoke as a means of communications.

Fire signals, lights in signal towers, and beacons were all early warning methods of impending invasion, such as during Napoleon’s threatened naval invasion of England in 1795. The Duke of Wellington organized regular mounted messengers that evolved into motorcycle dispatch riders in the 20th century.

History and the Royal Signals Military Museum

The History of the Royal Corps of Signals theme rooms trace the Corp’s evolution from men shouting to each other to modern radio transmissions. In 1870 the War office formed a Telegraph Battalion from the Royal Engineers, which served from 1884 into the late 19th century. Brightly polished vintage brass and wood telegraphs are displayed.

Two years after Alexander Graham Bell invented the telephone in 1876, the US Army began using telephones, of which several early telephones are exhibited including the C Mark 1 Ericsson portable military telephone, which weighs 18 lbs, the C Mark 2, D Mark 1, and D Mark 3 models. You’ll see many other antique pieces of communications equipment here. The Fullerphone, invented in 1916, had anti-eavesdropping capability and was used up to the 1950s.

The Admiralty Shutter Telegraph System display proved that even simple systems are highly effective. Three chains of huts with signaling frames and shutters were set up 5-10 miles apart running from London to Deal, Sheerness and Portsmouth in 1795. The purpose of this chain was to alert the Admiralty in London of an invasion by Napoleon’s Navy. This communications system was so fast messages took only 15 minutes to pass along the 238-mile chain from Plymouth to London. If the message was prearranged, it took only 3 minutes.

The History of the Heliograph tells how reflected sunlight was used to flash messages as long ago as the Greek and Persian Wars. They used polished shields as mirrors. Flags or banners were also used later. Depending on the size of the mirror used, messages could be sent over distances from 37-83 miles. Heliographs were used as late as 1941 during WWII.

A large number of World War I and II displays show how the Royal Signals Corps expanded, developed, and used improved communications equipment as the wars progressed. As the telephone became the prime means of communications the Royal Engineer Signal Service burgeoned from 6,000 to 70,000 by the end of the war. In World War II it mushroomed again to 8,518 officers and 142,472 soldiers, with 4,362 being killed in action.

As so often happens in world history, military inventions often become widely used in civilian life after a war ends. A great evolutionary step in military communications happened in World War II with the transition to Wireless radio because telephone wires were constantly cut by artillery fire. Wireless radio became commonplace in civilian communications after the war, thus shaping today’s communications.

Other World War II signalers used the civilian telephone system and dispatch riders. You’ll see a beautifully restored Triumph motorcycle and several other motorbikes with model signals riders in uniform.

As the Royal Signals reorganized and retrained in World War II, their equipment became more compact, lightweight and easier to operate as they geared up for the more mobile type of warfare. By now indispensable to all of the allied services, they worked with the Royal Navy as Beach Signals Units, or trained as parachutists to provide communications for commandos or Special Operations Executive (SOE) agents.

The SOE gallery explains the history and adventures of this brave group of spies, many of whom were caught and executed by the Germans. One of Churchill’s brain-children, he told it’s director to “set Europe ablaze”. Their mission: “to co-ordinate all action by way of subversion and sabotage against the enemy overseas”. By summer 1944 it had grown to 10,000 men and 3,200 women, of whom about 5,000 were field agents overseas in France, Germany, Holland.

SOE agents worked closely with the resistance forces, and used all manner of James Bond type secret agent equipment including plastic explosives, and limpet mines, and the Mark III suitcase radio set. Because the military radios were not suitable for clandestine operations, being too large and heavy, a range of radios were designed to fit into suitcases.

Polish technicians proved particularly adept at designing these “suitcase sets”, drawing from their pre-war experience. Despite the size and weight reductions the early A Mark II radio was made up of 3 metal boxes, all of which fitted neatly into a suitcase. It still weighed 22 lbs, and proved difficult for female agents to carry at speed over long distances. This model gave an output of 5 watts over 3-9 MHz. The next model, the A Mark III weighed only 8.8 lbs with a 5 watts output and 3.5 to 16 MHz frequency. Its range was 500 miles. Needless to say, all SOE operatives had extensive training in communications devices.

It was vital that the secret agents kept in touch with SOE HQ, for supplies to be sent. Members of the Royal Signals and Women’s Transport Service (known as FANYs) provided the staff for wireless operators and coders, playing a major part in their successful operations. You’ll see some suitcase wireless radios on display in this section.

The Second World War Wireless Sets display explains how military wireless sets had to operate a number of interference-free channels, have good ranges, must be robust, easy to operate, simple to maintain and portable. The 1943 Wireless Station No.10 is an example of such new equipment. It used radar techniques to beam 8 telephone channels over a duplex radio path between land links, being used after the D-Day landings.

This station was contained in a 4-wheel 2-ton trailer, one of which stands on exhibit. This was the technological wonder of its time using new and innovative techniques. It is the forerunner of the modern day radio relay equipment and the radiotelephone.

“Deception” shows how special signals units simulated radio traffic of whole Army Groups to deceive the Germans. Vans traveling around the Home Counties emitted vast volumes of fake wireless traffic simulating troop movements. Their illusion convinced the Germans that the US 3rd Army was in this area when they were 150 miles away in Cheshire.

Code-named Operation Fortitude, this operation was so effective the Germans held several of their divisions back around the Pas de Calais area for several weeks after D-Day. They believed another army would be landing at Calais because of the heavy signals traffic they were intercepting from these deception units.

Royal Signals were involved in every phase of Operation Overlord, the Invasion of Europe, and every aspect of the D-Day landings. Amongst their tasks were creating signals communications for the combined headquarters, communications for the assembly of troops for embarkation, creating fake radio traffic to deceive the enemy of the whereabouts of the landings, preparing cross-channel communications links, providing beach signals for the landings, allocating radio frequencies to ensure there was no unintentional jamming, and reestablishing telephone and telegraph lines once they had been captured and repaired.

As the Allies moved through Northwest Europe, Royal Signals laid hundreds of miles of telephone and telegraph cables. Communications to the United Kingdom were made via a cable laid under the Channel connected to signal stations at Bayeaux and Cherbourg.

The Airborne Forces Equipment display tells of the reliance of these paratroopers and glider-borne soldiers on wireless sets. The sets in 1942-43 had poor range, power, portability and robustness. New types of wireless were developed with these problems in mind, proving very successful. There’s an airborne wireless radio on display, and a small motorcycle that was also used for communications between the airborne force groups.

The Y Service Units were another clandestine intercept group, (albeit serving in England), staffed by Royal Signals men and women. They listened to enemy radio messages, noted them down and sent them to the huge Bletchley Park decoding center, which they knew only as “the big place”.

The Enigma Codes and Code Breaking gallery relates the history of Wartime codes and code breaking, centered at Bletchley Park. This gallery describes the German Code Encryption Machine, The Enigma. An authentic enigma machine is displayed here.

A display about the General HQ “Phantom” Liaison unit tells how its purpose was to keep allied Air Forces and artillery aware of where the front lines of Belgian and British troops were on the ground, in 1940. Using Armored cars, motorcycles, and radio sets, this group performed ground reconnaissance to locate the enemy forces.

After the evacuation of allied forces from Europe, the Phantom unit of 48 officers and 479 soldiers were tasked with the mission of observing possible sea-borne landing areas in Southern England. They were to give an early warning of the anticipated German invasion in late summer 1940. Some No.11 wireless sets they used are on display.

Another unusual clandestine group were the Auxillary Units, special groups of radio operators who were to remain behind in occupied Britain if the Germans invaded. They were to support resistance groups, and their long term survival chances were estimated to be slim. The sites and much information about this operation were kept secret until 1970.

The Far East Prisoners of War display tells how more than 100,000 Allied Prisoners of War were held by the Japanese and forced to work in extremely harsh conditions. A homemade receiver set used by the POWs to listen to allied radio news sits in a glass case.

An attention grabbing memorabilia exhibit displays sports trophies, ashtrays, cigarette cases, napkin rings, chess set, pocket-knives, water flasks, all made from shell casings. These glass cases also show Italian occupation money, Nazi badges, a fan signed by a POWs, cigarette packets, diaries, code pads, books, watches, first aid kits, egg cups, and more. The nearby Royal Signals Gallantry Awards Honors Board lists all Royal Signals soldiers who received medals for their bravery.

In addition, there are several more displays on Recent Conflicts and Wars since WWII including Malaya, Korea, Northern Ireland, the Falklands War, The Gulf War, Kosovo, Macedonia, Bosnia, etc. Several modern signals vehicles stand on display showing the evolution and increasing sophistication of these mobile headquarters.

The Pigeons at War display pays homage to this plucky little bird in military communications. They carried military messages as early as 1815, for Wellington at the Battle of Waterloo. In WWI, 22,000 pigeons flew in service, from 150 mobile lofts, with 400 loftsmen to tend them.

When you go there - visitor information:

You’ll need your passport to enter The Royal Signals Museum because it’s located in the Blandford Camp Army Base. A soldier gets on the bus at the entrance to the camp, checks your passport then gets off as the bus exits the other end of the camp. Don’t let this put you off visiting a superb signals museum.

Transport to Royal Signals Museum: easiest to travel by car, although it can be reached by bus from Salisbury or Weymouth. The 30-minute bus ride from Salisbury through the English countryside is most enjoyable, giving one a chance to see the small towns, green fields, hedges, and narrow country roads typical of rural England.

Viewing Time:2-3 hours.

Return from Royal Signals Museum to Communications

Return from Royal Signals Museum to Home Page