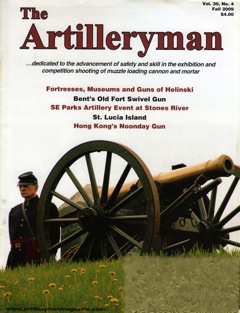

Suomenlinna

Sveaborg Island Fortress,

Helsinki, Finland

By Roy Stevenson

Suomenlinna: Military Fortresses,

Museums and Guns

Imagine six rocky islands, joined together by causeways, where you can stroll around 4 fortresses, 4 military museums, a submarine, and gun batteries so numerous that you literally trip over them everywhere you walk. The Suomenlinna Sveaborg Island Fortress, built to protect the entrance to Helsinki harbor, is as close to nirvana as military, fortress and artillery aficionados will ever get.

One of the largest sea fortresses in the world, Sveaborg has enough militaria attractions to keep you entertained for the best part of a day. Here you’ll see several gun batteries, a museum covering the construction of the fortresses, another museum filled with ship models and weapons, another packed with coastal artillery, and a military museum crammed with tanks, artillery, uniforms, weapons and dioramas, and a 1933 submarine that you can walk through.

I decide to visit this well publicized series of islands because it sounds too good to be true for a military historian. From downtown Helsinki’s Market Square, I board the small ferry for the 15-minute trip across to the island. Debarking onto the quay in front of the Jetty Barracks on Stora Oster Svarto Island (also known as Iso Mustasaari) I follow the map I’ve been given to the Suomenlinna Museum. It tells how the fortress was constructed, and describes daily life of the garrison town on this island. Sveaborg was a bastion fortress, formed by four enclosed fortresses, each on a separate island. Through a wide screen presentation, reader boards, exhibits of uniforms, paintings and other historical artifacts, I learn that construction of the fortresses started in 1748 by the Swedish, who at that time occupied what we now know as Finland. Some interesting displays of cannon balls and muskets hint at exciting things to come in the other museums.

Until 1808 Sveaborg was the largest fortress in the Swedish realm. Until that date it was the region’s main defense center for protecting Sweden’s interests, also housing a large naval base. After the 1808-09 War between Russia and Sweden, it changed to Russian hands for the next 110 years. A graphic painting depicts the fiery bombardment of 1855 during the Crimean War between Britain and Russia. Starting on August 9, the fortress was fired upon continuously for 47 hours by British Naval ships that were out of range of the fortress’ guns. The fortress was blasted by more than 1 million kilograms of incoming ammunition, with spectators standing on the shore at Helsinki describing the scene as “ a frightening spectacle of muzzle flames and billowing smoke, flares and numerous fires”.

Continuing through the island’s history, I see that Finland finally gained her independence in 1918, and the fortress became a Finnish garrison. Today several hundred Finns live on the islands—a kind of maritime suburb—and it’s one of the country’s most visited tourist attractions.

A couple of minutes’ walk gets me to the second museum on my map, the red brick Manege Military Museum. This cavernous hall is filled with military artifacts and dioramas portraying Finland’s national defense story after its independence. Old World War one monoplanes, Finnish anti-aircraft guns, military vehicles and armored tanks, pre world war two howitzers, a mock up diorama of a Finnish military bunker in the forest, made from pine logs, historical photographs, lengthy reader boards, a wheeled food wagon, and many other interesting exhibits catch my eye for a solid hour.

I cross the bridge over the choppy, gray channel water to Vargon Suisaari Island to the gray cobblestone road leading to the rambling remains of the Ehrensvard Crown Castle. The museum in Count Ehrensvard’s former home, a series of high-ceilinged rooms, is stocked with historical paintings, antique wooden furniture, beautifully rigged, three feet tall models of three-mast boats, old chests, and swords and cannon balls.

Outside I walk around the impressive, massive granite fortifications of Crownwork Ehrensvard, the largest on the island. The fortress has an outer closed ring of 16 bastions with another inner ring of 9 bastions. Its low central bastion has two brick wings surrounding a courtyard that encloses the Count’s tomb. Numerous loopholes are built into the granite walls for small arms defense. Two sandstone framed gate vaults have the Swedish coat of arms engraved above them. Several vaulted embrasures in the casemate wall are accessible to curious visitors.

The fortress aficionado can find all the elements of a classical European bastion in the island’s four fortresses: sloped fortress glacis, artillery platforms, covered ways and moats, bastions, caponiers, traverse walls and counterguards, and vaulted connection corridors and galleries for short-range defense. Most of the fortresses have at least four parallel defense lines situated one behind the other, usually at different levels, that enabled their guns to be fired simultaneously. And most of these fortifications are interspersed with ditches. Formidable defenses indeed!

Walking along the wind-swept central road that traverses the spines of the islands I notice big guns lying randomly around, set up to defend the fortresses, or standing in rows in the courtyards, and dug into casemates. I see two interesting bronze Russian howitzers in the Crownwork Ehrensvard courtyard that closely resemble German Krupp howitzers of the 1880-1890 era. These rifled, breech loading guns have bore liners protruding from the front, with setscrews locking them at 12 o’clock. If you look closely at the iron carriage near the ground, you’ll see it’s parallel to and close to the ground. My gun expert, Mr. Clair Stairett of Olympia, Washington, after looking at my photos, tells me these guns were probably fired from this carriage with wheels, making them ideal for coastal defense.

Next on my list is the Coast Artillery Museum, on the northern shore of adjacent Gustavssvard Kustaanmiekka Island. Situated in an old gunpowder magazine that was built in 1776, this red brick building, with granite archway over the entrance, still has the original brick vaults and ventilation ducts. The magazine is built into a protective earth wall and designed to withstand direct hits from heavy cannon. Outside, it’s guarded by two aged, interesting looking guns. The closest one in the picture is a long barreled heavy Russian siege gun or coastal gun from around the turn of the 19th century. It’s probably a 120-mm/4.2 inch breechloader, with recoil cylinder mechanism barely perceptible under the carriage.

Inside the museum stand a wide variety of guns and ammunition spanning three centuries, including early cannon, turret guns, shells, historical photos and maps, even missiles and motorized artillery. More recent range finding and fire direction equipment are also displayed. Three ancient bronze cannon stand on racks alongside each other. The topmost one is almost certainly a 17th century English Culverin cannon. Note the ornate and high “dolphin” handles, and the two bumps on either side of the touchhole; a hinge point and latch point for a protective vent cover. The center cannon, without handles, is likely an iron cannon of the 18th or early 19th century. At bottom is a hefty, later model iron gun.

Back outside, I wander off the central road to what looks like an intact gun battery on the western edge of Gustavssvard Kustaanmiekka Island. Sure enough, I find the Russian sand banks and gun batteries; a special coastal defense line built in the latter half of the 19th century. It’s a long sandbank with adjoining gun batteries and ammunition cellars dug into the sand banks. The guns are placed on masonry bases behind the sand bank. Three of these coastal mortars are 11-inch, the eight others 9-inch, set on gliding mounts, placed on an upper and a lower section transverse wedge. The lower section moves sideways on wheels and is fixed to the base by a large pivot. When the gun is fired, the upper section glides back and upwards on the lower one, absorbing the recoil. The redesign of the larger rear diameter of these Russian mortars obviously had this in mind. These were originally German (Krupp) inventions and sold to Scandinavia and Russia. Eventually the Russians adapted and manufactured them under license—in this case N. Maijevskiy designed them—and they were manufactured in the perm gun works in 1873.

The 9-inch guns had a range of 6.4 kilometers for their 122.8 kg steel shells, and 10Kilometers for the 250 kg shells from the11-inch bore. The rifled gun barrels have several steel mantles within each other. The rate of fire was 1 round every 3 minutes. Technically, these guns are a bit long to call mortars, and they did not elevate enough to drop projectiles downward onto enemy ships, but they were often called mortars to strike fear into the enemy.

Doubling back on Suisaari Island I follow signs to the Submarine Vessikko museum. I’m expecting a submarine floating on the channel waters, but am surprised when I round a corner and see the bow of a large submarine standing on dry land. This 250-ton monster was built in 1933 by the Dutch, for the German navy, but transferred to the Finnish Navy in 1936. It saw some patrol and convoy action in World War Two from its shipyard base here on the Island. You can walk through the entire submarine and see its well-preserved equipment.

You can spend an entire day clambering over the fortresses, admiring the guns, and strolling through the excellent museums on these islands. There are a number of restaurants spread though the islands. If you go to Suomenlinna Fortress dress warmly with a windbreaker and be prepared for some hiking, so wear solid walking boots.

Return from Suomenlinna Fortress to Military History

Return from Suomenlinna Fortress to Home Page