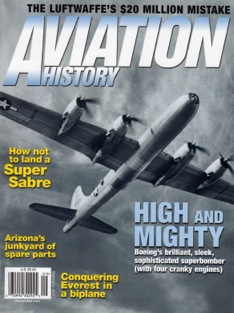

The Boneyard

Where U.S. Aviation History Lives On

By Roy Stevenson

Walking among 4,050 retired military aircraft up close and personal is a once-in-a-lifetime experience—one to be long remembered. Your first thought, as you pass row upon row of white painted warbirds arranged in precise herringbone patterns on Arizona’s sun-bleached Sonora Desert, is that it’s like walking through a massive graveyard—so it’s no wonder the 309th Aerospace Maintenance and Regeneration Group (AMARG) at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base, just south of Tucson, has acquired the nickname, “The Boneyard”.

Aged fighters, bombers, and support aircraft—many of them decades old—stand menacingly atop the packed gray dirt. Warm, gentle wind stirs flapping pieces of canvas, and whistles across loose antenna wires. Tufts of short, dried brown grass sprinkle the ground, and the occasional tumbleweed drifts past the silent behemoth aircraft. A long-eared jackrabbit springs off into the distance between the massive hulks of two B-52 Bombers, an absurd juxtaposition of nature and machines of war.

A tour of the Boneyard is an eerie, nostalgic walk through the pantheon of U.S. military aviation history. Almost every type of aircraft from the U.S. Air Force, Army, Coast Guard, Navy, Marine Corps, and even NASA, has “done time” here awaiting its fate. The aircraft stored at AMARG are worth $32 billion, a figure calculated when they were brand new, so today’s value would be considerably higher.

Over 100 different conventional fighters, bombers and support aircraft stand like Titans of the air at AMARG, representing 70 different weapons systems, plus a few surprises—like former presidential helicopters, Century series fighters, a D-21 drone for an SR-71 Blackbird spy plane, and former Luftwaffe aircraft. Toss in a couple of MIGs, some converted military commercial aircraft, the gondola from the Navy’s sole surviving post-World War II airborne early-warning blimp, and the odd Titan II missile re-entry vehicle lying around (hopefully deactivated) and your visit to AMARG makes an interesting experience.

Why are all these military aircraft here at the Boneyard? What happens to them? How much are these aircraft worth? And how many of these bad boys have seen combat?

The Boneyard’s story starts immediately after World War II, in 1946, when the U.S. military had stockpiles of thousands of fighting aircraft, primarily B-29s and C-47s, and no war to fight. The fighters and bombers had to be stored somewhere as a strategic reserve, and the 4105th Army Air Force Unit at Davis-Monthan Army Air Force Base offered an ideal location because of its low humidity, low rainfall, and high altitude (2,550 feet), all of which minimize rust and corrosion. The hard alkaline topsoil, about 6 inches thick, with a clay-like sub layer called “caliche”, also provides an ideal platform for moving heavy aircraft around without having to pave large areas. The two B-29s that dropped the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki were stored here.

In 1964 Davis-Monthan AFB was designated the Military Aircraft Storage and Disposition Center (MASDC), where all surplus military aircraft were to be consolidated. After the withdrawal from Vietnam in the 1970’s, the total aircraft stored here reached a staggering high of 6,080. In 1985, with the site, now performing a number of additional tasks: aircraft reactivation (aka regeneration), aircraft overhaul (maintenance), refurbishing, reclaiming or cannibalizing parts for consolidation, storage of aircraft to be sold to foreign military air forces, reconfiguring aircraft as drone aerial targets, destruction and disposal of aircraft under various treaties, and production tooling storage, it was renamed the Aerospace Maintenance and Regeneration Center (AMARC).

Most recently, in 2007, the Boneyard facility was renamed the 309th Aerospace and Regeneration Group or 309 AMARG, under the 309th Maintenance Wing at Hill AFB, Utah. Despite the designation as a squadron, of the 1,011 people working for AMARG, only two are active-duty Air Force personnel. Many of the civilian employees have served in or are retired from military service, most with aircraft maintenance experience ranging from ground maintenance, fuels, supply, and comptrollers.

A vehicle is required to tour the Boneyard. It’s 2,600 acres, or 4 square miles, so walking along row after row of aircraft under the blazing Arizona sun would take all day, and of course the base is a restricted working air force base. The bus tour of AMARG is your best bet—it leaves from the nearby Pima Air & Space Museum

The Boneyard tour drives along “Celebrity Row”, a three-quarter mile long paved road where one model of each aircraft stored at AMARG stands on display. The ghost aircraft are lined up along both sides, with signs in front of each indicating its type. It’s like touring an open-air aviation museum, and the stories of some of these aircraft are fascinating.

The Lockheed L-130 Hercules VXE6 Phoenix (tail #8321), for example, was embedded in ice in the Antarctic for 17 years while working on Operation Deep Freeze, for the National Science Foundation. The Hercules crashed on the ice following a mishap with a rocket-assisted take-off system, which the crew survived. The Navy declared the aircraft a write-off, and the Herc sank deep into the ice, until only its tail and propeller tips were visible. In 1971, it was dug out, repaired, and flew for another 10 years before retiring to AMARG, still in top condition.

The F-14 Tomcat, (#159437), was one of two Tomcats from carrier USS John F. Kennedy that shot down two Libyan MIG-23 Floggers over the Gulf of Sidra on January 4, 1989, in a rather brief but exciting dogfight. The Floggers appeared to be aiming straight for the two Tomcats, despite the Tomcats maneuvers to indicate they were not looking for trouble. The Floggers continued on a hostile path, and the Tomcats loosed AIM-7 Sparrow missiles first, which took one of the MIGs out, followed by an AIM-9 Sidewinder missile which torched the second MIG.

In 1979, C-141 Starlifter (#40614) from the 53rd Military Airlift Squadron lost two engines directly after takeoff from Richmond, Australia, en route to Alice Springs. The number three engine failed, and then a turbine blade split and flew off into number four engine, which also failed. A fire broke out in the cargo hold, filling the aircraft with thick smoke. Captain Trosky took control, veered towards a nearby riverbed to avoid hitting the town of Richmond, but then headed towards the airport. The Starlifter landed trailing engine parts and fuel, all crewmen surviving unhurt.

The row of Sikorsky CH-53D Sea Stallions at the Boneyard would have some tales to tell. Some of them were used to transport of U.S. presidents off the White House lawn. None of the technicians working on these Sikorskys knew exactly which ones transported the presidents, or which presidents were in them, but it was fun to stand there and imagine what might have transpired in their cabins—some high drama for sure!

What becomes of the Boneyard aircraft? AMARG uses a four-tiered system used by AMARG. Type 1000 aircraft are here for long-term storage, to be maintained until recalled to active service, should the need arise. Type 1000 aircraft are termed inviolate; meaning they have a high potential to return to flying status and no parts may be removed from them. These aircraft are “represerved” every four years. The Type 1000s include hundreds of F-16s that are scheduled to become remotely flown drone targets in the near future. Nearly 1,000 aircraft have been processed here for conversion into drones since 1976; mainly F-102 Delta Daggers, F-100 Super Sabers, F-106 Delta Darts, and F-4 Phantoms.

Type 2000 aircraft are used as “aircraft storage bins” for parts, to keep other aircraft flying. The majority of the aircraft stored at AMARG are Type 2000s. In 2010, 309 AMARG reclaimed 13,342 parts with an original value of $557.1 million. The crews pull the parts, then seal the aircraft back up. Fuel is drained from the aircraft and replaced with lightweight 1010 oil, which is drawn through the engines by running them for a short time. The oil is then drained.

Next, the aircraft goes through a wash rack for a thorough cleaning and moved to an area where their escape systems and ejector seats are deactivated. Then, the aircraft are sealed with several coats of materials. A black plastic tape covers cervices in the canopy seams and the engine inlets and outlets are covered with aluminized cloth, which is taped into place. A car wax-like material is applied to the canopy or cockpit plexiglass, and the aircraft is sprayed with two coats of black latex material. Finally, a white vinyl coat called “Spraylat” is sprayed to seal the aircraft, which helps with internal temperature control.

Type 3000 aircraft are kept in near flyable condition in short-term, temporary storage, and are simply waiting at the Boneyard pending transfer to another unit, sale to another country, or reclassification to the other three types. Currently there are no Type 3000 aircraft in storage at MARG.

Some Type 4000 aircraft have been gutted and nearly every useable part has been reclaimed. They will eventually be broken down into scrap, smelted into ingots, and recycled. These aircraft are considered “excess to the needs of the aircraft manager” and parts may be reclaimed to support any Department of Defense branch or government agency. They may eventually be broken down into scrap, smelted into ingots, and recycled, or become museum exhibits at places like the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, or the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force.

The boneyard is such an impressive sight that it was incorporated into the movie Transformers II: Revenge of the Fallen. The 4,050 aircraft stored here would make it the second largest air force in the world, a humbling thought, which begs the question; if these are obsolete U.S. military aircraft, how many aircraft are currently active on our air force bases? As of 2009, the U.S.A.F. operates 5,573 manned aircraft (3,990 U.S.A.F; 1,213 Air National guard; and 370 Air Force Reserve).

Bus tours of AMARG leave from the adjacent Pima Air & Space Museum, the largest private air museum in the U.S.A. and the third largest overall, with over 250 aircraft sprawled over 250 acres. This museum, combined with the AMARG bus tour, is as good as it gets for aviation history buffs.

Return from The Boneyard to Military Articles

Return from The Boneyard to Home Page